WHAT’S THAT SLOP YOU’RE EATING?

The late great Norm Macdonald, not long before his own death from leukemia, mused about the proclivity to describe such dying as “losing the battle with cancer.” He famously remarked, “I’m not a doctor, but I’m pretty sure that when you die, the cancer dies too. That’s not a loss, that’s a draw.” Mr. Macdonald battled his own cancer privately for almost 10 years before calling it a draw; generative AI has been suffering from the cancer cell model of infinite growth for a shorter period, but its prognosis is rapidly growing grim. I’m not a tech bro, but I’m pretty sure that when human intelligence dies, the AI models and billionaire investors will die, too. Let’s hope the economy and the planet can break even.

IT'S LATER THAN YOU THINK

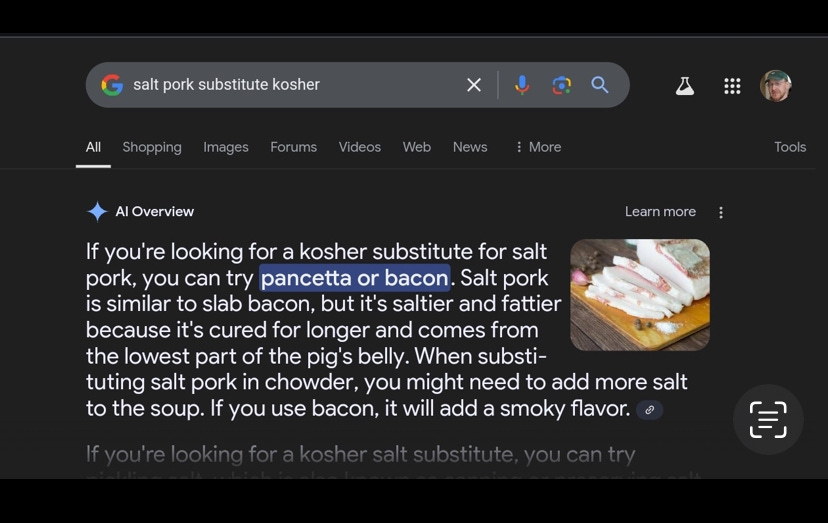

How bad is it? Consider that slop—defined as “Art, writing, or other content generated using artificial intelligence, shared and distributed online in an indiscriminate or intrusive way, and characterized as being of low quality, inauthentic, or inaccurate”—is one of six finalists for this year’s Oxford Dictionary Word of the Year (voting started 11/14, cast yours here). Said slop is a leading cause of another top contender: brain rot—"deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as a result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.” And the leading cause of said trivial, if not downright inaccurate, information is rapidly diminishing training data available to teach AI models beyond their current capabilities.

The effects of that rapidly diminishing training data are of course already apparent. Earlier this year Microsoft’s MyCity chatbot answered queries from prospective entrepreneurs in New York City by advising them they could and should take a cut of their workers’ tips and fire employees if they complained about sexual harassment. A month later Elon Musk’s chatbot Grok tweeted that NBA star Klay Thompson had thrown bricks through a string of houses in Sacramento, CA. Grok is suspected of hallucinating the false accusation after being fed data about Thompson “throwing bricks,” a basketball term for missing shots badly.

Indeed, it seems everyone has their own anecdotes about AI misses, from Google searches that recommend adding glue to a pizza recipe to eating rocks for their nutritional value. These epic fails and many other problems with AI chatbots are a direct result of the diminishing value of internet data available for training. When AI scraping can find no more real information, chatbots are by default trained on AI generated content, which is then itself used as training data, and the cycle of eating its own tail continues.

AI developers who seek to address these problems with more and more powerful models are having a tough go. Techradar reported earlier this month that “OpenAI is running into difficulties with Orion, the next-gen model powering its AI.” Indeed, all AI developers are coming up against hard limits in their attempts to realize performance gains similar to those achieved with earlier new releases. That limit is training data. Microsoft’s OpenAI, Google’s Gemini, Anthropic, and other AI developers have to date scraped enormous datasets to train their models but those memes from 2005 weren’t wrong—even the internet is not infinite.

Finding unused, high-quality data that can be used for training is becoming more difficult and thus more expensive. But if the little data still available does not significantly improve the product’s capabilities, it’s hard to charge more for it. Some in the industry have expressed that developing generative AI models much beyond their current capabilities may be “financially unfeasible.”

CAN THEY, LIKE, DO THAT??

There is also increasing concern that the process of scraping data for training has ethical and legal implications. The LLM (Large Language Model) engines behind ChatGPT and similar generative AI products require enormous amounts of data to train. That data primarily comes from scraping the web, a process that uses bots to harvest information from web sites by extracting their html code. AI web scrapers use machine learning and natural language processing to mine the data. More importantly, AI scrapers can get around anti-scraping systems such as CAPTCHAs and IP blockers, among others. This makes them uniquely capable of violating ethical standards regarding consent and transparency and intellectual property and copyright.

To even talk about “collecting data” frames the debate in ways that favor AI firms. The tech industry uses such terms to suggest that data is out there like wild berries and scrapers are just gathering what the natural landscape provides. But there is no data until someone scrapes it—it’s content, and content does not exist “in the wild.” It must be created, and like farm produce, is the result of the labor of many. Yet AI farmers continue to reap what others sow with little if any consequence for what is in reality theft (Rowenna Fielding--Miss IG Geek).

A common practice is AI data laundering. To avoid violating protections for the web content they scrape, commercial enterprises contract with non-profit organizations to mine the data. The non-profits, whose actions might be permitted under the Fair Use Doctrine, then create databases from the scraped content and pass it to the commercial entity. This is how Stable Diffusion, the leading text-to-image generator, was able to harvest massive amounts of content from creators at Pinterest, Flickr, WordPress, and other sites without their consent or knowledge.

Similarly, Meta’s AI powered Make-A-Video system for generating video from text was trained on over 10 million video clips scraped from Shutterstock, along with another 3,000,000 Microsoft scraped from YouTube. To bypass consent and copyright stipulations, the actual data mining was done by the Visual Geometry Group at the University of Oxford, with whom Meta and Google contracted. And in a move that can only be seen as desperation, Microsoft recently began scraping data from its customers’ Word documents, a clear violation of informed consent and transparency.

MORE POWER MR. SCOTT

Serious as ethical, legal, and financial limitations are, the most formidable constraint facing further AI advancement is the simple lack of computing power to do more and more intensive training. Rumors of the death of Moore’s Law were not exaggerated; the number of transistors that engineers can fit inside computer chips might still double roughly every two years, but the computing power of the average chip no longer increases at the same rate. To achieve greater power, tech firms instead now seek to construct ever larger server farms. Right now, several companies are working on building data centers with power levels between 50-150 megawatts. For context, 100 megawatts would power Dayton, OH for a month. Estimates are that to power the next level models of generative AI will require training clusters of one gigawatt, or 1000 megawatts, the amount of energy produced by your average nuclear power plant. Dr. Emmett Brown’s calculations notwithstanding, we are many years away from building such data centers, for a variety of reasons.

Obtaining permits to construct such enormous server farms requires navigating endless layers of regulation regarding not merely zoning but also water use, energy consumption, and how to dispose of vast amounts of waste heat from the GPUs. And once built, data from the training clusters must be sent out across transmission lines that cover private and public land, which requires more permits. Again, because time is money, these issues add greatly to the cost of producing better AI. All things considered, the cost to build a one-gigawatt data center is projected to be one trillion dollars.

Which brings us back to the prohibitive cost. The launch of ChatGPT in 2022 started an AI arms race among competitors and their investors. “Perhaps the biggest concern for AI investors is that we’ve yet to see any AI startups make a profit. Will they ever be rewarding for investors? Thomas Anglero, founder and CEO of Too Easy AS, thinks not. ‘None have been profitable and will not be ever,’ Anglero told GOBankingRates.”(yahoo finance). American investors have now sunk so much capital into AI—over $68 billion in 2023 alone--that the prospect of failing to see a return on that investment within the next year or two would hit the tech sector hard. The five largest AI stocks -- Microsoft, Nvidia, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta Platforms – now trade at an average of 49 times forward earnings, a lofty height from which to crash. And because tech is such a large component of the stock market today, the large-scale exodus of cash caused by AI’s failed promise would likely trigger a larger market bubble burst similar to the 2000 dot.com crash.

NO MORE WATER FIRE NEXT TIME

Yet continuing to invest in and develop AI technologies has costs other than financial. Large scale AI models are the world’s most resource-intensive digital technologies. Enormous clusters of servers for AI training generate tremendous amounts of heat and require vast quantities of water to cool. How much? In Virginia, where the world’s largest concentration of data centers is now housed, water consumption jumped over 60% from 2019 to 2023. Perversely, much new building is centered around the Greater Phoenix area, where in 2023, the city suffered its hottest summer in over 1000 years and residents in eastern parts of the area had no tap water for a year due to low water volume in the Colorado River. Nor does the environmental impact end there.

The massive data centers now powering AI also release significant amounts of CO2 into an already warming climate, and the problem is likely far worse than imagined. Actual emissions from data centers owned by AI leaders including Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Apple, were about 662 percent higher than what they've officially reported, and those reports only covered 2020-2022, a period that does not include the boom created by ChatGPT (The Guardian). And it will only get worse. By 2030, AI server farms are projected to consume 1743 Terawatts (1,743,000 gigawatts), or 10 times the amount of energy Earth receives from the Sun every day. Generating that much electricity would discharge 829 million tons of CO2, an amount equal to emissions from the global iron and steel industries (Forbes). Just building the servers will add another 74 million tons of CO2. The lifecycle of the GPUs (graphical processing units) that support AI is 2-3 years, so new hardware must be continually manufactured, further adding to AI’s carbon footprint. Given these realities and projections, Microsoft’s promise to be “carbon neutral by 2030” is just more hot air.

All that remains to be seen is which will go boom first—the tech bubble or the planet. Meanwhile we’re playing for the draw. Like Norm.