BACK TO THE LAND

While planning a now long-ago trip to London, I came across photos of old neighborhoods in a guidebook. On close inspection, many of the houses shown had windows that were boarded up or covered with brick. The guidebook explained that in 1696, William III of England introduced a property tax requiring those living in houses with more than six windows to pay a levy. This prompted homeowners to cover up all but six windows to avoid paying the new tax. Some evidence suggests this may be the origin of the term daylight robbery, and the lack of light that resulted from the tax certainly stole good health and hardihood from the urban poor due to a condition the French named “the British sickness.”

At first the window tax struck me as just another of those odd quirks of history, like Archduke Ferdinand’s wrong turn that led to WW I or why Hiroshima was chosen as a bomb target. Yet in truth the window tax is but one instance of countless tax policies that created many unintended and often undesirable consequences over the years. And still do.

Most American towns and cities have a property tax composed of land value plus the value of improvements made to that land. After the Second World War, local governments preferred such taxes because they generated a lot of revenue from the newly built properties in rapidly developing suburbs. Cities such as Los Angeles and Atlanta reaped large tax rewards as they spread out rather than up. But tax systems that worked 70 years ago are failing those same cities and others like them today. Indeed, property taxes as currently levied have a host of negative effects on many urban neighborhoods no less dire than Britain’s archaic window tax.

THE PROPERTY TAX PROBLEM

URBAN BLIGHT

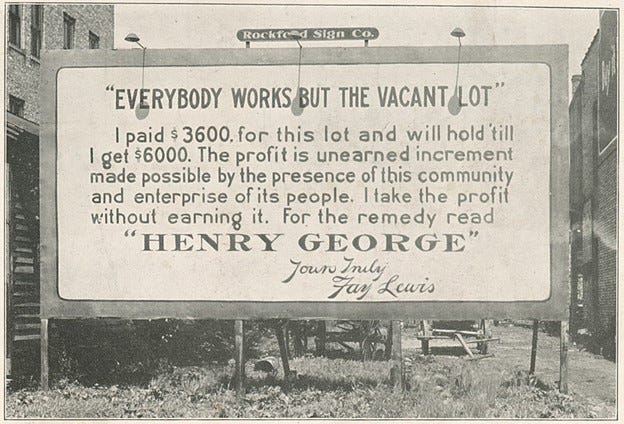

Property taxes in their current form create a system whereby collectively produced value is captured almost exclusively by private entities. Specifically, urban communities have generated tremendous economic value over the years. Increased property values in downtowns result primarily from three collectively produced factors: land productivity and scarcity, availability of public services such as police and fire protection, transit systems, etc., and the growth of nearby communities (e.g. suburbs) that provide cities with consumers who patronize their businesses and fill their coffers with parking fees, sales tax revenue, and other income. Yet most of that value is sucked up by untaxed rising land values and of course rents, allowing landowners to capture a windfall of unearned income.

This was the case with the city of Allentown in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. In 1982 when Billy Joel wrote his song lamenting its demise its condition was indeed bleak. Yet after WW II and into the 1960’s it was a boom town. Its population peaked in 1963, and good union jobs created a thriving middle class. The demise of domestic steel production and other large manufacturing industries in the 1970s, however, led to a precipitous decline in Allentown’s fortunes and population. Remaining property owners faced increasing tax burdens as people and businesses fled the city for surrounding suburbs and vacant buildings fell into disrepair.

THE HOUSING CRISIS

And many buildings stayed that way because another negative consequence of traditional property taxes is the disincentive to improve existing property. Upgrading existing property is punished by the levy of higher tax rates while owners who let theirs continue to decay pay less, creating the conditions that allow slumlords rather than neighborhoods to thrive. Furthermore, property owners forced to sell at distressed prices often do so to real estate speculators who hold on to lots or decaying buildings for years, paying little tax while waiting for the neighborhood to improve. Properties that sit idle in this way are unavailable for productive use, especially housing. This dynamic is a major factor contributing to the current housing crisis in urban areas. When speculators eventually reap the rewards of rising property values, the cycle of private capture of collectively produced value continues. This often manifests as rising rents that displace longtime residents who can no longer afford to live in such gentrified neighborhoods.

THE LAND VALUE TAX SOLUTION

It doesn’t have to be this way. A well-known alternative tax system—the Land Value Tax (LVT)—has existed for well over 100 years and is designed to not only fix the problems already mentioned but also benefit communities in additional ways. It’s not a theoretical fix, either; we already have real world data showing how well it works in cities from Allentown to Altoona to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. Also Scranton. And Titusville. You’ll notice that these municipalities have something in common besides an understandable love for Wawa and Sheetz (mostly Wawa). They are all in Pennsylvania, which is one of just three states whose governments have empowered local communities to utilize the LVT.

THE LVT EXPLAINED

The LVT, also called the single tax movement or Georgism, originated with the American economist Henry George, author of Progress and Poverty (1879). Just as it sounds, a land value tax is levied on the value of the land component of property only (unlike traditional property taxes that include the value of land plus all improvements). In practice, cities that have replaced traditional property taxes with an LVT have instituted a split-rate tax. Instead of taxing the combined value of land, buildings, and other improvements at a single fixed rate, the split-rate tax levies substantially higher rates on the value of the land itself. This discussion will refer to split-rate systems as LVTs.

For context, all property taxes are based on a mill rate equal to one 10th of a percent. To calculate property tax, multiply the property's mill rate by the assessed property value and divide it by 1,000. This means a traditional property tax of 30 mills on a property assessed at $600,000 would require the owner to pay $18,000 annually. With an LVT of 10 mills on buildings and improvements valued at $300,000 (equal to $3000) and 20 mills on land valued at $300,000 (equal to $15,000), the owner would pay the same total of $18,000. As we will see, IRL most property owners pay substantially LESS tax under an LVT system.

LIVING HERE IN ALLENTOWN

That was exactly what happened in Allentown about 15 years after Billy Joel sang the sorry story of the once-proud city. In 1996 Allentown adopted an LVT that replaced their traditional combined property tax with one that taxed land at a rate of 5.038% while the rate for buildings and improvements was set at 1.072%. Unlike the hypothetical example above, this new system resulted in a tax decrease for over 70% of property owners. In the most at-risk neighborhoods such as those built before WW II and industrial areas, over 90% of parcels saw their tax bills go down. Importantly, the total tax revenue collected by the city remained the same. And market investment soared. Within four years of introducing the new LVT, the number of building permits rose over 30%, eclipsing that of its sister city, Bethlehem.

By 2020, Allentown had not only recovered from decades of urban decay, it became the fastest growing city in Pennsylvania according to that year’s census data.

THE HARRISBURG MIRACLE

An even more dramatic turnaround can be seen in Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania capital. In 1982, Harrisburg was deemed the second most distressed city in the United States by Federal distress standards. The city adopted an LVT in that same year that taxed land at a rate four times higher than buildings and improvements. The new tax system reduced the tax burden for over 90% of property owners in the city. It also increased incentives for owners to improve their parcels since there would be no tax penalty for doing so.

As a result, “from 1982 to the end of 2009 [there was], $4.8 billion worth of investment, thousands of new jobs were created, and over 40,000 building permits were issued.” Additionally, the number of vacant lots in the city fell by 80%, the tax base rose from $212 million to $1.6 billion, and the crime rate fell 46%. (A Land Value Tax for London, February 2016). The number of businesses also increased: in 1982, just 1908 businesses operated in the city, but that number ballooned to more than 8800 by 2019. Finally, the taxable value of properties in Harrisburg rose from $212 million in 1982 to 1.6 billion by 2010 (Non-glamorous gains: The Pennsylvania Land Tax Experiment).

BUT WHAT ABOUT…?

In light of the many benefits the LVT model provides, the obvious question is why more cities have not adopted it. There are some objections to LVTs, but given widespread bipartisan support for adopting them among politicians, government officials, and economists, it remains somewhat of a mystery that more cities and towns have not done so.

Some have argued that LVTs would cause rents to increase. Standard economic theory does indicate that taxing something decreases its supply due to the greater cost of production. But the supply of land is fixed (you may have heard they’re not making any more of it), so taxes do not impact its supply. Thus, in economic terms an LVT is highly efficient.

Other objections stem from the potential challenges of implementing a land value tax given the need for municipalities to assess land and improvements separately. The simplest solution to this concern is to use the subtraction method. Assessors can estimate the combined value of land and improvements per the traditional property tax system and then subtract the replacement cost of buildings to isolate the value of the land.

I saw this method in action two years ago when I switched insurance companies. The new company sent an agent to look at our property and give me a quote for what they would charge to insure it. After a cursory inspection, the agent gave us his property value estimate, which was 60% higher than what we paid for the house just six years ago. When I asked how much our premium would go up based on that value, he said “Not at all. The cost to replace your house is the same as it was six years ago. It’s the land value that’s gone up in this neighborhood. If your house burns down, you won’t need to replace the land.”

And yet as mentioned earlier, there are just three states in which land value taxes are approved, and only one—Pennsylvania—where they are utilized. This is primarily due to what are known as uniformity clauses. Many states have a constitutional requirement that taxes be applied uniformly within a given municipality. The primary opponents of LVTs are large landowners, particularly those in distressed areas of cities who pay little on their valuable land under the current combined property tax system. These property owners can mount court challenges based on state uniformity clauses to try to prevent towns and cities from adopting LVTs. However, since 1893, no court has struck down a land value tax based on a uniformity clause.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

Traditional property taxes as applied to most American cities and towns serve communities no better than did Britain’s archaic window tax. Rather than disease and poor health, the effects of this outdated tax are a nationwide housing shortage, skyrocketing rental rates, alarming increases in office vacancies, and decaying downtowns. The only winners are large landowners and corporations who live off the fat of rising land values they do not create. It’s time to return that value to those who do by implementing land value taxes more widely, by George.